The lessons you learn teaching an iconic video game character to rack up points–without mowing down ghosts–might serve a higher purpose.

![]()

Since his 1980 debut in arcades, the world has considered Pac-Man to be a good guy—maybe even a hero. But did you ever stop to consider the possibility that his habit of chomping on cute little ghosts might be offensive rather than admirable?

Me neither—until I talked to some IBM researchers who decided to look at the game that way as part of an experiment in artificial intelligence and ethics with implications that might go way beyond bending how we look at an old video game. IBM discussed this work during a Fast Company Innovation Festival Fast Track session today at its Astor Place office in New York City.

IBM uses the term Trusted AI to cover ethical issues relating to the technology as well as matters of security and general robustness, which will be increasingly vital as we ask software to make decisions with potentially profound impact on human beings. As it builds AI systems, IBM is investigating questions of how to “teach our ethical norms of behaviors and morality, but also how to teach them to be fair and to communicate and explain their decisions,” says IBM fellow Saska Mojsilovic.

Already, there are plenty of real-world examples of why these subjects are worth worrying about. Earlier this month, for instance, Reuters’ Jeffrey Dastin reported on an AI-infused recruiting system developed by Amazon. The company scrapped the tool after it saw that it was penalizing female candidates—for instance, actively downgrading job hunters with the word “women’s” in their résumés—in part because it had been trained using data from past Amazon hires that—typically for engineering positions—skewed heavily male.

Concerns over AI systems behaving inappropriately are only growing as more of them gain skills not by mimicking human experts but rather by testing billions of possibilities with blinding speed and devising their own logic to achieve a goal as efficiently as possible. One AI designed to play games such as Tetris, for instance, found that if it paused the game, it would never lose—so it would do just that, and consider its mission accomplished. You might accuse a human who adopted such a tactic of cheating. With AI, it’s simply an artifact of the reality that machines don’t think like people.

There’s still tremendous upside in letting AI software teach itself to solve problems. “It’s not about telling the machine what to do,” says research staff member Nicholas Mattei. “It’s about letting it figure out what to do, because you really want to get that creativity . . . [The AI] is going to try things that a person wouldn’t maybe think of.” But the less software thinks like a human, the harder it becomes to anticipate what might go wrong, which means that you can’t just program in a list of stuff you don’t want it to do. “There’s lots of rules that you might not think of until you see it happen the way you don’t want it,” says Mattei.

GHOST EATER NO MORE

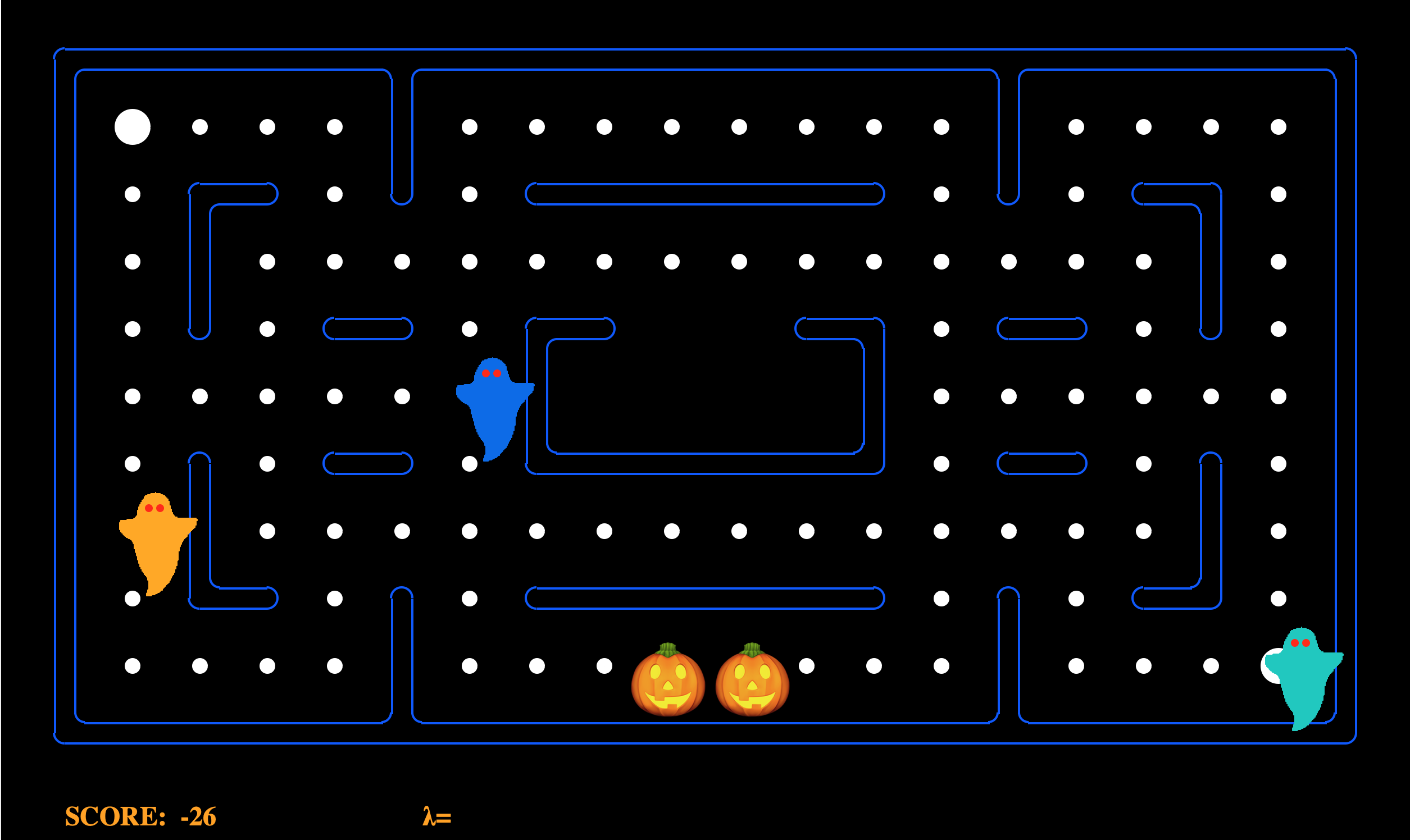

As IBM’s researchers thought about the challenge of making software follow ethical guidelines, they decided to conduct an experiment on a basic level as a project for some summer interns. What if you tried to get AI to play Pac-Man without eating ghosts—not by declaring that to be the explicit goal, but by feeding it data from games played by humans who played with that strategy? That training would be part of a special sauce that also included the software’s unconstrained, self-taught game-play techniques, giving it a playing style influenced by both human and purely synthetic intelligence. Stepping through this exercise, IBM’s researchers figured, might provide insights that would prove useful in weightier applications of AI.

IBM chose Pac-Man as its tapestry for this experiment partly out of expedience. The University of California, Berkeley has created code for an instrumented version of Pac-Man designed for AI studies; the company was able to adapt this existing framework for its purposes. (Teaching AI to play Ms. Pac-Man is a separate science unto itself, and a more imposing challenge, given the game’s greater complexity.)

The researchers built a piece of software that could balance the AI’s ratio of self-devised, aggressive game play to human-influenced ghost avoidance, and tried different settings to see how they affected its overall approach to the game. By doing so, they found a tipping point—the setting at which Pac-Man went from seriously chowing down on ghosts to largely avoiding them. (For the purposes of the videos below, IBM avoided any possible infringement on Pac-Man’s intellectual property by ditching the familiar characters in favor of Halloween-themed doppelgangers.)

As the AI played Pac-Man, the researchers saw it get smarter about switching off between the two game-playing techniques. When Pac-Man ate a power pellet—causing the ghosts to flee—it would play in ghost-avoidance mode rather than playing conventionally and trying to scarf them up. When the ghosts weren’t fleeing, it would segue into aggressive point-scoring mode (which also involved trying to avoid the ghosts, since touching one would cost Pac-Man a life).

In the end, the value of the project was the insight IBM gained about Pac-Man’s thinking process as he traveled the maze and made trade-offs between trying to score the maximum number of points and avoiding doing harm to the ghosts: “We opened up his brain a little bit,” says Mattei. The company is currently considering how to apply the lessons it learned to other games and broader AI experiments.

Wherever this particular research project leads, IBM has already begun taking steps to instill ethical behavior into shipping software, both with its own products and AI Fairness 360, an open-source tool kit it created for avoiding bias in AI-powered applications such as facial recognition and credit scoring. “We are not only being able to address these problems with research questions, but we are actually now moving them into real-world applications,” says Mojsilovic. “And that is really big.”